If you’ve met me for more than a few minutes you’ve heard me talk about my passion project, Leave the House Out of It (lthoi.com). If you’ve really paid attention to my blog posts you’ve caught that a couple years ago I rearchitected the app to move to an event-based, serverless architecture on AWS. After a year of not doing very much with the project I’ve had the itch to make some upgrades (more on this next year). Before I did, I wanted to upgrade the CI/CD pipeline I use to manage the code.

While I had moved away from containers/EKS, I did keep the containerized Jenkins that had been deployed alongside my code on the EKS cluster. I got an EC2 server, installed docker, and deployed the image there. Unfortunately, on an EC2 server Jenkins quickly became both disproportionately expensive and pretty slow. The cost was due to the inefficiency of running a Jenkins server for an app you deploy infrequently. In fact, because the app was all serverless and low volume, I was actually paying more for my Jenkins server then for all of the rest of my AWS charges combined. In spite of the cost, the performance was pretty terrible. Jenkins lost access to deploy agents across my cluster and instead churned away on an under powered EC2 server. This caused larger runs of the pipeline to take upwards of 9 minutes.

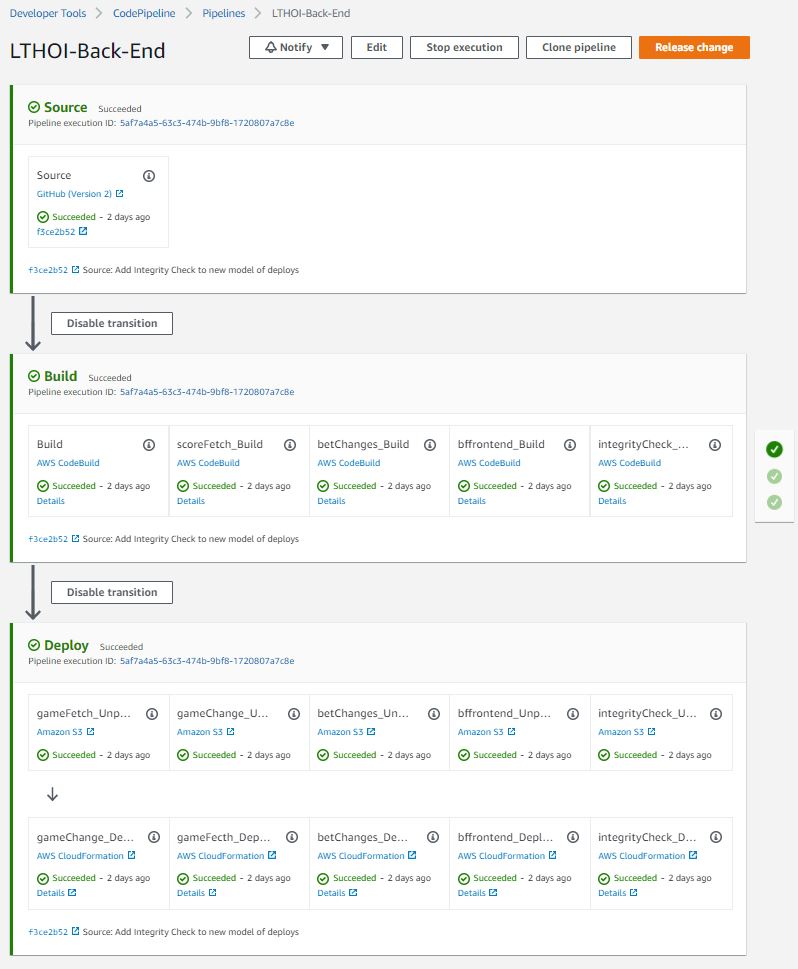

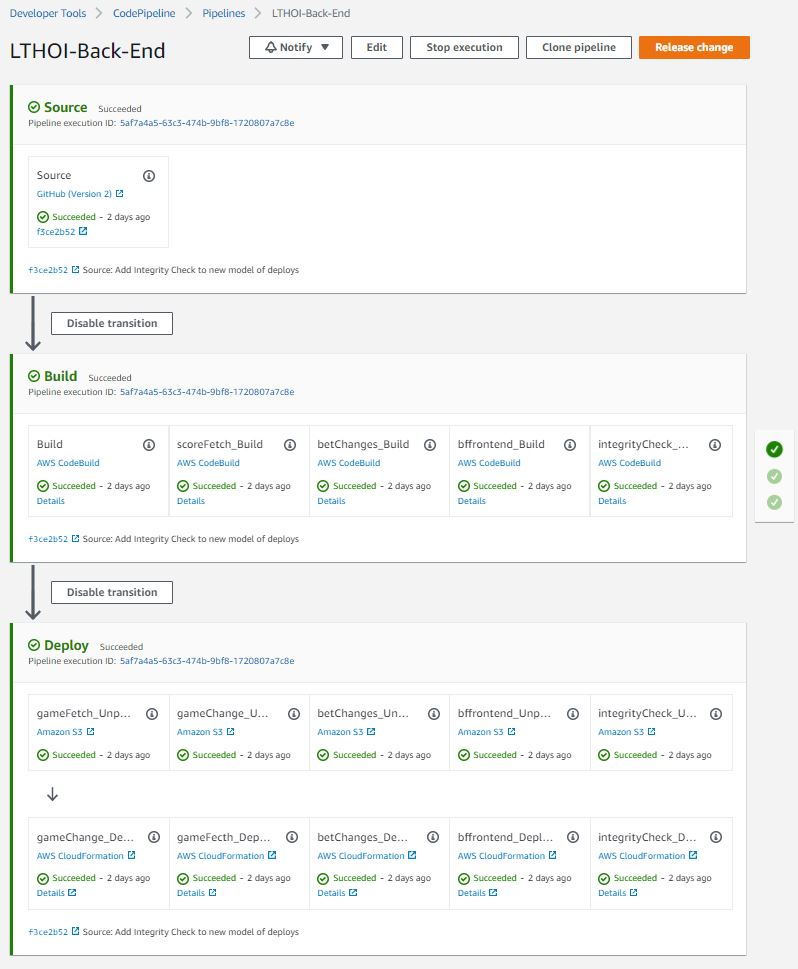

Over the last few weeks, I’ve taken the final step to the AWS native world and adopted CodeBuild, CodeDeploy, and CodePipeline to replace my Jenkins CI/CD pipeline. My application has 5 Cloud Formation stacks (5 separate Lambda functions along with associated API gateways and DynamoDB databases) and an S3 bucket and CloudFront implementation that hosts the Angular UI. I ended up with 6 separate CodeBuild projects, one to build and unit test each of the lambdas and one to build the UI. The one that builds the UI I took a shortcut and simply used the build service to also deploy. For the 5 lambdas, I wrapped them in a CodePipeline along with AWS CF Deploy jobs for each.

The only tricky part I found was that I did not want to refactor my lambdas in to an “Application” so I could not use AWS CodeDeploy out of the box. That made it difficult to use the artifacts from AWS CodeBuild. The artifacts are stored as zip files meaning I can’t directly reference them from the CloudFormation for Lambda which is expecting a direct address of where it can find the .jar file (I wrote the Lambdas in Java). I got around this by having two separate levels of “deploy”. In the first one, I use an S3 “action provider” to unzip the build artifact and drop it in an S3 bucket that I can reference from the CloudFormation. The resulting code pipeline looks like this:

The results are compelling on several fronts:

- I was able to shutdown the EC2 instance and all the associated networking and storage services. It should save me a total of ~$50. It looks like on normal months I’ll be in the free tier for all of the Code* tools. So it will literally be $50/month right in my pocket. I expect all but the biggest software development shops are going to better with this model than with dedicated compute for CI/CD.

- In my case, I also sped up the process considerably. I had been running full build and deploys in around 9 minutes. This was due to the fact that I was using one underpowered server. AWS CodeBuild, is running 5 2 CPU machines for build and running my deploys concurrently. That has dropped my deploy time to about 1.5 minutes. (note: In fairness to Jenkins, I could have further optimized Jenkins to use agents to deploy the AWS stacks in parallel… I just hadn’t gotten around to it)

- The integration with AWS services is pretty nifty. I can add a job to deploy a particular stack with a couple of clicks instead of carefully copying and pasting long CLI commands.

- In addition, this native integration makes it easier to be secure. Instead of my Jenkins server needing to authenticate to my account from the CLI, I have a role for each build job and the deploy job that I can give granular permissions to.

There are very few negatives to this solution. It does marry you to AWS, but if you have well written code and a well documented deployment process it wouldn’t take you long to re-engineer it for Azure DevOps or back to Jenkins. It’s definitely going to be my way forward for future projects. Goodbye Groovy.